Some of the pioneering transplantation work in human

SCI involved the transplantation of embryonic tissue into the spinal-cord

cysts of patients with posttraumatic syringomyelia. Basically, with this

disorder, a cyst or syrinx develops at the injury site which extends over

time up and down the cord, in turn, potentially resulting in the further

loss of function. Such function-compromising cysts, which can develop many

years after injury and rehabilitation, are obviously salt-in-the-wound

demoralizing to the individual. Although MRI-imaging indicates that

nearly 60% of individuals with chronic SCI have small, nonexpanding cysts,

3-8% have expanding cysts with some neurological loss.

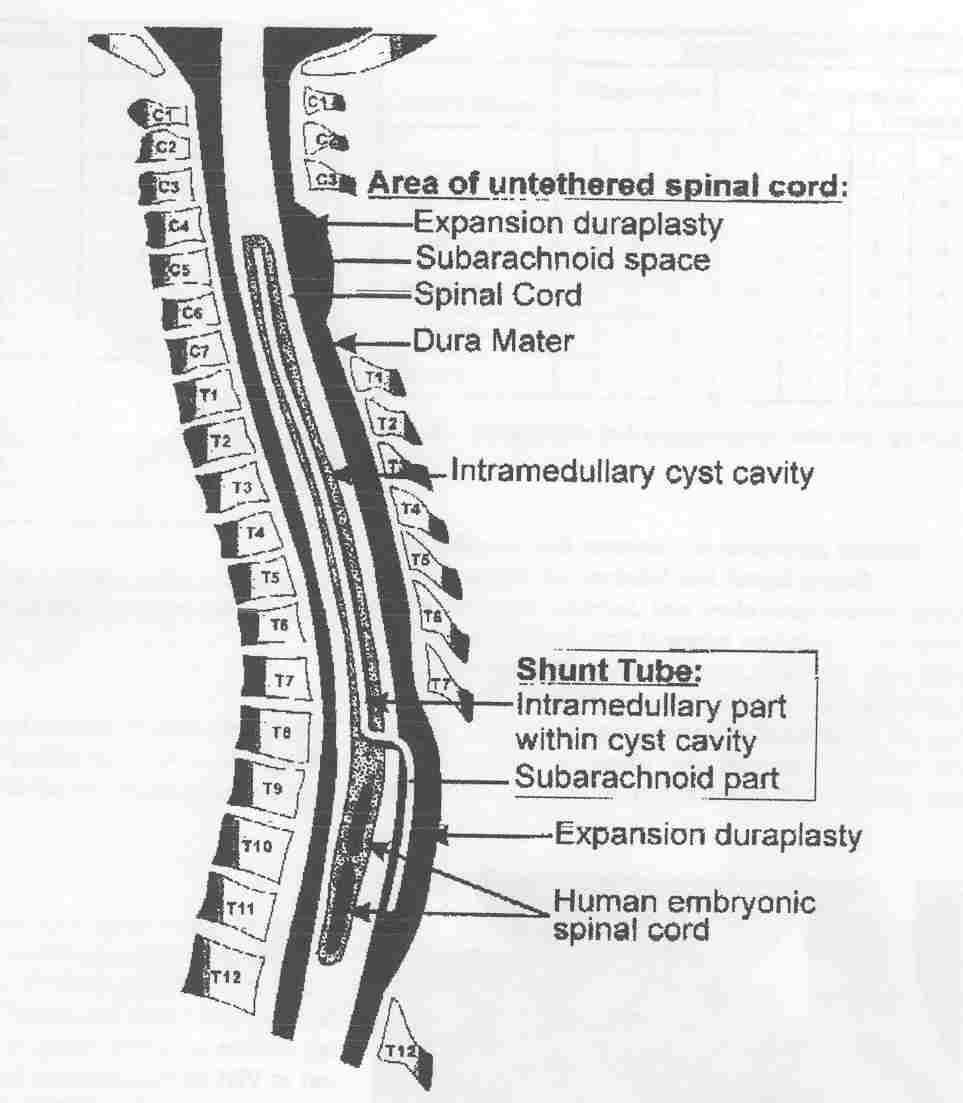

Traditionally, syringomyelia cysts associated with

the loss of neurological function often have been treated by placing a

fluid-draining shunt into the cyst and/or the surgical untethering of

movement-restricting scar tissue that fixes the cord to the dura, which,

in turn, promotes cyst expansion.

1) Dr. Scott Falci and colleagues (Denver,

Colorado, USA and Stockholm, Sweden) inserted embryonic spinal-cord

tissue in the syringomyelia cyst of three patients with SCI. The first

was a 49-year old male who sustained a complete C4 injury in 1990. In the

year before surgery, he had lost additional sensory, motor, and

respiratory function and had increased spasticity and pain. MRI imaging

revealed a 20-cm cyst essentially the width of the spinal cord that

descended down from the C4 to T11 vertebral level.

In addition to placing a fluid-draining shunt into

the cyst and untethering the spinal cord, three human embryonic spinal

cord pieces were inserted end-to-end in the cyst’s lowest 6-cm section.

The embryonic spinal cord tissue was obtained from two aborted fetuses of

7.5- and 9-weeks gestation.

As shown by MRI imaging over a seven-month follow-up

period, the cyst was obliterated in the section of tissue implantation. In

contrast, in the area where the shunt tube was placed (i.e., no tissue

implantation), the cyst was smaller but had not collapsed. Although the

patient recovered some lost function, due to the intervention’s

multi-component nature (i.e., shunting, untethering, & implantation), the

recovery could not be attributed merely to embryonic tissue implantation.

2) Dr. Edward Wirth, III and colleagues

(Florida, USA) have also implanted fetal spinal-cord tissue into the cysts

of patients with progressive posttraumatic syringomyelia. Specifically,

the investigators have reported the results of implanting this tissue into

the first two patients of 18 enrolled in a preliminary safety and

feasibility study (J Neurotrauma 18(9), 2001). The fetal

spinal-cord tissue used for transplantation was 6-9 weeks gestational age.

After cyst drainage and detethering, small tissue fragments were implanted

into the cyst cavity.

Patients were followed for 18 months using

ASIA-assessment standards, MRI imaging, and neurophysiological testing.

Although it was difficult to determine if the implanted tissue survived,

collapse of the cysts was limited to areas in which the tissue was

specifically placed. Although functional improvements were subtle, study

results indicated the absence of procedure-related adverse effects. The

investigators concluded that the transplantation of fetal spinal-cord

tissue into syringomyelia cysts is “logistically feasible and procedurally

safe.”

TOP